Posts Tagged ‘malpractice’

Falsifying Medical Records and Identifying Missing or Misleading Information

Saturday, February 27th, 2021

Falsifying medical records is no easy feat. Proving that it has occurred can be just as challenging. Patient medical records are legal documents with federal and state laws governing their management. Any appearance of medical record tampering or inappropriate altering can lead to investigations and can impact legal proceedings relying on records as evidence. …read more

Kennedy Terminal Ulcer – A 2016 Update

Sunday, October 23rd, 2016

2016

In April 2016, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel or NPUAP announced a change in the terminology and the stages of pressure injuries. Though these stages continue to include both unstageable pressure injuries and deep tissue pressure injuries the new definitions do not specifically mention the Kennedy Terminal Ulcer. Over the years, however, multiple panels and advisory groups have documented the Kennedy Ulcer as an end of life phenomenon.

The unavoidable skin breakdown that occurs as part of the dying process, known as a Kennedy Ulcer, has been recognized by Ostomy Wound Management since a 2009 journal article. Also in 2009, an expert panel released a consensus statement known as SCALE or Skin Changes At Life’s End which identified skin organ compromise occurring at the end of life. The panel recognized that the ulcer is usually seen on the coccyx or sacrum but has been reported in other anatomical areas and is usually associated with imminent death.

This special classification was also mentioned by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2014 within its Quality Reporting Program Manual and its Continuity Assessment Record and Evaluations Data Set (CARE) for long-term care hospitals. The “Coding Tips” of the publication noted if an ulcer was part of the dying process, developing from six weeks to two to three days before death, it should not be coded as a pressure ulcer.

Click here for the full detailed staging guidelines.

ALN Consulting will continue to stay on top of these and other developments. Contact ALN Consulting if you have questions about a case and would like an initial consultation.

2015

This portion originally published on October 26, 2015:

It is well known that a pressure ulcer is an area of skin that breaks down when pressure on the skin reduces blood flow to the area. However, the knowledge and acceptance of skin failure at the end of life from various etiologies, including the Kennedy Terminal Ulcer (KTU), is growing among evidence based practitioners. The Kennedy Terminal Ulcer and other unavoidable similar skin phenomenon such as Skin Failure, SCALE (Skin Changes at Life’s End), Deep Tissue Injury (DTI), and the Tremblay-Brennan Terminal Tissue Injury were addressed at the most recent VCU Pressure Ulcer Summit by experts and scholars in the field.

The Kennedy Terminal Ulcer was first described by Karen Lou Kennedy in 1989, and evidence of poor perfusion to the skin causing a pressure ulcer-like damage of soft tissue in serious illness and at the end of life is well documented. While there are several etiologies that could cause unavoidable skin failure, the Kennedy Terminal Ulcer is focused on soft tissue injury on bony prominences, usually on the sacrum, during the dying process.

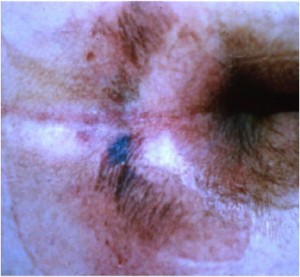

As illustrated in the photos, the Kennedy Terminal Ulcer has a sudden onset of a purple/red blister or abrasion, and rapidly progresses to a Stage III or IV ulcer. While further research is required, and was recommended by the PU Summit, there is general consensus that if a dying patient has blood perfusion issues that affect many other organs, known as multi-organ failure, then it is reasonable to accept that the lack of blood perfusion also can affect the skin resulting in unavoidable soft tissue injuries, despite adequate prevention measures.

Kennedy Terminal Ulcer

A phenomenon called “3:30 Syndrome” presented as a subdivision of the Kennedy Terminal Ulcer, which forms more quickly and appears as black spots.

The classic “butterfly” or “horseshoe” shape of the Kennedy Terminal Ulcer.

In the near future the ANCC Magnet commissioners plan to develop and create access to a Magnet Designated Facility Database for hospital acquired pressure ulcers (HAPU) to promote ongoing research for unavoidable pressure ulcers and uncharacteristic soft tissue injuries that occur despite appropriate implementation and escalation of interventions to prevent skin injury and ulcers at the end of life.

References

- Brindle, Creehan, Black, & Zimmerman. (2015). The VCU Pressure Ulcer Summit: Collaboration to Operationalize Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcer Prevention Best Practice Recommendations. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nursing, 2015:00(0):1-7.

- Kennedy-Evans, Karen. (2012). The Life and Death of the Skin. [Nursing Home/ALF Litigation Seminar].

- Kennedy Terminal Ulcer. (2014). Retrieved October 7, 2015, from Kennedy Terminal Ulcer web site: http://www.kennedyterminalulcer.com/

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) Release New Clinical Guidelines and Taxonomy for Pressure Injuries

Friday, October 7th, 2016

In 1986, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) was formed as an independent, non-profit organization established to ensure consistent prevention, management and research of pressure ulcers. Conflicts in research and prevention created the need for this governing body, an organization that would work to create guidelines and establish best practices surrounding pressure injury wounds. NPUAP serves as the authoritative voice for improved patient outcomes in pressure ulcer prevention and treatment through the development of public policy, education and research.

Subsequent to the formation of NPUAP, the terminology to describe “pressure ulcers” was redefined and the staging system of pressure wounds expanded. Although changes were made with the intent of clarifying the differences among the stages of pressure ulcers, the new classification system led to more confusion. For example, the use of the term “injury” and “ulcer” interchangeably caused great confusion.

In April 2016, a consensus conference was convened by NPUAP to review and revise the pressure injury staging system and to standardize the terminology used to describe injury to the skin from external pressure. The term “pressure ulcer” was changed to “pressure injury.” This simple change in terminology was actually monumental, as it was a major departure from the old taxonomy in the 30 years since the panel was formed. Updates to the panel’s description of the stages of pressure injuries were developed. The group indicated that the change in terminology would more accurately describe pressure injuries to both intact and ulcerated skin.

The 2016 definition of “Pressure injury” by NPUAP describes localized damage to the skin and underlying soft tissue usually over a bony prominence, related to a medical procedure such as prolonged surgery or from a medical device. The injury can present as intact skin or an open ulcer and may be painful. The injury occurs as a result of intense and/or prolonged pressure or pressure in combination with shearing forces. The tolerance of soft tissue for pressure and shear may also be affected by microclimate, nutrition, perfusion, co-morbidities and condition of the soft tissue. Shearing occurs from friction against the skin that leads to a superficial or partial thickness injury, often resembling an abrasion.

Pressure Injury Staging

The staging system further defined pressure injuries of stages 1-4 as well as including medical device related pressure injuries and mucosal membrane pressure injuries. The following illustrations denote each stage and classification of pressure injuries.

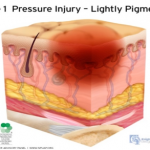

Stage 1 Pressure Injury: Non-blanchable erythema of intact skin. Intact skin with a localized area of non-blanchable erythema, which may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. Presence of blanchable erythema or changes in sensation, temperature, or firmness may precede visual changes. Color changes do not include purple of maroon discoloration; these may indicate deep pressure injury.

Stage 1 Pressure Injury: Non-blanchable erythema of intact skin. Intact skin with a localized area of non-blanchable erythema, which may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. Presence of blanchable erythema or changes in sensation, temperature, or firmness may precede visual changes. Color changes do not include purple of maroon discoloration; these may indicate deep pressure injury.

Stage 2 Pressure Injury: Partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis. The wound bed is viable, pink or red, moist, and may also present as an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Adipose (fat) is not visible nor are deeper tissues. Granulation tissue, slough and eschar are not present. These injuries commonly result from adverse microclimate and shear in the skin over the pelvis and shear in the heel. This stage should not be used to describe moisture associated skin damage (MASD) including incontinence associated dermatitis (IAD), intertriginous dermatitis (ITD), medical adhesive related skin injury (MARSI), or traumatic wounds (skin tears, burns, abrasions).

Stage 2 Pressure Injury: Partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis. The wound bed is viable, pink or red, moist, and may also present as an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Adipose (fat) is not visible nor are deeper tissues. Granulation tissue, slough and eschar are not present. These injuries commonly result from adverse microclimate and shear in the skin over the pelvis and shear in the heel. This stage should not be used to describe moisture associated skin damage (MASD) including incontinence associated dermatitis (IAD), intertriginous dermatitis (ITD), medical adhesive related skin injury (MARSI), or traumatic wounds (skin tears, burns, abrasions).

Stage 3 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin loss. Full thickness loss of skin, in which adipose tissue is visible in the ulcer, meets the definition of a Stage 3 pressure injury. Granulation tissue and epibole (rolled wound edges) are often present. Slough and/or eschar may be visible. The depth of tissue damage varies by anatomical location; areas of significant adiposity can develop deep wounds. Undermining and tunneling may occur. Fascia, muscle, tendon, ligament, cartilage and/or bone are not exposed. If slough or eschar obscures the extent of tissue loss, this becomes an Unstageable Pressure Injury.

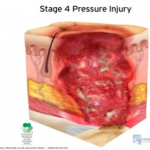

Stage 4 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin and tissue loss. Full-thickness skin and tissue loss occurs with exposed or directly palpable fascia, muscle tendon, ligament, cartilage or bone in the ulcer. Slough and/or eschar may be visible. Epibole, undermining and/or tunneling often occur. The depth of the injury varies by anatomical location. If slough or eschar obscures the extent of tissue loss, an injury such as this would be described as an Unstageable Pressure Injury.

Stage 4 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin and tissue loss. Full-thickness skin and tissue loss occurs with exposed or directly palpable fascia, muscle tendon, ligament, cartilage or bone in the ulcer. Slough and/or eschar may be visible. Epibole, undermining and/or tunneling often occur. The depth of the injury varies by anatomical location. If slough or eschar obscures the extent of tissue loss, an injury such as this would be described as an Unstageable Pressure Injury.

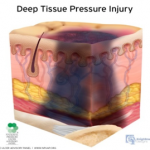

Deep Tissue Pressure Injury: persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon or purple discoloration. This type of injury may involve either intact or non-intact skin, presenting with a localized area of persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon, purple discoloration or epidermal separation revealing a dark wound bed or blood filled blister. This injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure and shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury, or may resolve without tissue loss.

Deep Tissue Pressure Injury: persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon or purple discoloration. This type of injury may involve either intact or non-intact skin, presenting with a localized area of persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon, purple discoloration or epidermal separation revealing a dark wound bed or blood filled blister. This injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure and shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury, or may resolve without tissue loss.

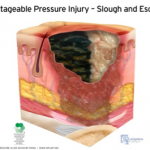

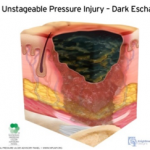

Unstageable Pressure Injury: Obscured full-thickness skin and tissue loss. This type of injury involves full-thickness skin and tissue loss. The extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar. If the slough or eschar is removed from the wound, a stage 3 or stage 4 pressure injury will be revealed. Stable eschar on the heel or ischemic limb should not be softened or removed.

Unstageable Pressure Injury: Obscured full-thickness skin and tissue loss. This type of injury involves full-thickness skin and tissue loss. The extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar. If the slough or eschar is removed from the wound, a stage 3 or stage 4 pressure injury will be revealed. Stable eschar on the heel or ischemic limb should not be softened or removed.

As classifications and guidelines change, it’s critical to have an expert on your team who understands the current definitions. ALN Consulting’s team of legal nurse consultants have their finger on the pulse of these changes, and are trained to spot inaccuracies in medical records that can effect case outcomes. Contact ALN Consulting today to learn how we can help.

ALN Litigation Perspective

Monday, October 3rd, 2016

Fudge & McArthur, P.A.’s Donna Fudge and Benjamin Broadwater announce victory in recent Stage IV Pressure Ulcer/Nursing Home case in Florida.

The complexity of circumstances demonstrated in this case is not atypical of the facts in many of the long-term care cases in litigation today. The importance of cohesion between the medical and legal defense teams cannot be emphasized enough in these cases. From both a clinical and legal standpoint, considerable skills are required to weed through the minutia of what was likely an abundance of medical records and break down the case facts simply into a bad outcome despite the rendering of good care. Of significance in this case was the team’s ability to use the medical record to create the picture of collaborative care provided in the absence of wound documentation. Unfortunately, all too often we see key portions of the medical record are missing, requiring our nurse consultants to hunt for the pieces of the puzzle necessary to reconstruct the plan of care and develop a fail-safe defense strategy.

Defense Jury Verdict: Morgan & Morgan, P.A. represented the Estate of Willie F. Coley, in a lawsuit against TR & SNF, Inc., d/b/a The Nursing Center at University Village, and BVM Management, Inc. in relation to Mr. Coley’s 12+ year residency at University Village’s skilled nursing facility. The Complaint alleged negligence for the development of a Stage IV sacral/coccyx pressure ulcer. Mr. Coley passed away 15 months after leaving University Village and continued to have this pressure ulcer until the time of his death. A graphic photograph of the Stage IV ulcer was shown to the Jury.

This case focused on the final three months of Mr. Coley’s 12+ year residency at University Village. Plaintiff alleged that University Village failed to implement appropriate interventions after re-admission from a hospital stay, and failed to revise any interventions after Mr. Coley developed his sacral/coccyx ulcer, in violation of the Federal Regulation for pressure ulcers, FTag 314. Plaintiff also alleged that the caregivers failed to follow the Facility’s own Policies and Procedures by failing to monitor/track the wound, and by failing to provide adequate pressure relief every 2 hours. As a result, Plaintiff alleged that University Village failed to prevent the development, and worsening, of Mr. Coley’s pressure ulcer. Lastly, Plaintiff alleged that the University Village caregivers failed to properly assess and treat Mr. Coley for Pain allegedly associated with his wound

Defense Themes: The defense focused on Mr. Coley’s 10 most recent Hospitalizations leading up to his coccyx skin wound and his 20 underlying Comorbidities including a history of cerebrovascular accident, stercoral ulcer, dementia, paralysis, C. difficile, and GERD which contributed to Mr. Coley’s development and eventual worsening of his sacral/coccyx ulcer. The Defense proved that proper interventions were put in place when Mr. Coley was re-admitted from the hospital, but despite these interventions, Mr. Coley experienced an unavoidable “Friction Blister” that progressed to a pressure ulcer and eventually became a Stage IV with suspected osteomyelitis. The jury heard expert testimony that the healing of Mr. Coley’s left and right Buttocks skin wounds, adjacent to his Coccyx sore, was evidence that he was being properly offloaded in that area. The Defense argued that it met FTag 314 by: (1) evaluating Mr. Coley’s risk factors for additional pressure sores, (2) implementing interventions for the prevention of pressure sores, (3) monitoring the impact of those interventions by notifying the physicians of changes in the wound and obtaining new treatment orders such as a wound vac and an infectious disease consult, and (4) revising those interventions.

Overcoming Documentation Problems: The nursing home had lost its wound tracking documentation. However, the Defense argued that any lack of documentation did not mean that there was a lack of monitoring. The staff consistently notified Mr. Coley’s physicians of changes in the wound’s condition, and a wound care physician was tracking the wound on a weekly basis from April 23, 2014 through June 4, 2014. The Defense pointed out to the jury that Plaintiff’s allegations were based on records that were “cherry picked” and it was explained that, in order to get a true and accurate understanding of the interventions such as re-positioning, pain management and wound monitoring by the caregivers, the jury had to look at the entirety of Mr. Coley’s Chart, which was filled with evidence that these areas of care were actually provided.

Jury Verdict: Following the 5 day jury trial, the jury returned a defense jury verdict in favor of both Defendants.

Trial Team: Donna Fudge and W. Benjamin Broadwater of Fudge & McArthur, P.A. were lead trial counsel. Caitlin Kramer, Esq., and Paralegals Amy Bozarth and Julie Christ of Fudge & McArthur, P.A. assisted in the trial.

Defense Experts: Dr. Aimee Garcia (Houston, Texas) and Alexa Parker Clark (St. Petersburg, Florida)

It’s the complex cases such as this one which demonstrate the essential need for synergy between the medical and legal defense teams. ALN Consulting’s team of experts are trained to quickly identify key pieces of evidence that are missing or have been falsified. We can piece together a solid picture from numerous records, giving legal teams a clear path to case resolution.

ALN Consulting is a national provider of medical-legal consulting services, founded in 2002. Our expertise includes, yet is not limited to, medical malpractice, long-term care, product liability, class action/mass litigation, and toxic tort. Contact Us to put our legal nurse consulting experts on your case.

Uncovering False Allegations

Wednesday, August 3rd, 2016

ALN was presented with a long term care case with allegations related to respiratory failure and death. At the time of the events in question, the plaintiff, Ms. Maggie White, was an 84-year-old female with a past medical history of coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, anxiety, Alzheimer disease, chronic low back pain and lumbar disc degeneration. Ms. White was admitted to the defendant facility, a skilled nursing center, for rehabilitation after receiving epidural steroid injections for chronic low back pain.

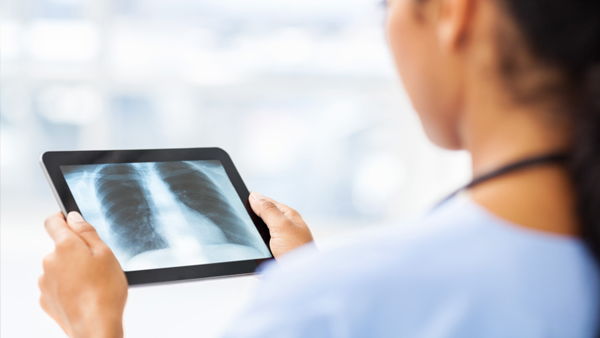

Upon admission, care was implemented to include physical therapy and occupational therapy. During the course of residency, Ms. White developed a cough which progressed to chest congestion with decreased breath sounds. Prescribed treatment included cough suppressants, antibiotics, nebulizer treatments, and steroids. Ms. White’s chest x-ray was clear; her respiratory symptoms improved with treatment, but subsequently developed edema of the lower extremities bilaterally. Lasix was prescribed which resolved the extremity edema. Three days later, Ms. White was again found to have diminished breath sounds and labored respirations requiring a hospital admission. Admitting diagnoses included congestive heart failure (CHF) and cardiomegaly with respiratory failure. Ms. White was intubated and placed on ventilator support. Despite multiple consultations and treatments, Ms. White’s CHF worsened and she expired three days later.

Plaintiff’s counsel alleged that the defendant facility failed to properly assess Ms. White’s respiratory status and failed to provide timely treatment for shortness of breath, alleging the symptoms existed for days prior to transfer. Plaintiff’s counsel further alleged her respiratory failure and death were caused by the defendant facility’s negligence.

False Allegations Identified With Legal Nurse Review

Upon review of the facility records, ALN’s nurse reviewer was able to refute allegations of inappropriate assessment, as well as the existence of respiratory distress in the days prior to transfer. The investigation confirmed that the facility staff properly assessed, reported, and monitored Ms. White’s clinical status per facility protocol and long-term care guidelines. Although it was believed this information was enough to present an adequate defense, the ALN nurse reviewer dug deeper into the hospital records, striving to ensure the best possible defense was developed for the client.

Further investigation into Ms. White’s condition and circumstances surrounding her death revealed a myriad of possible contributing/causative factors. Ms. White had a recent diagnosis of possible heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). Research revealed that the most common complication of HIT is venous thromboembolism, including pulmonary embolism. Subsequent to Ms. White’s hospital transfer, the nurse reviewer’s investigation revealed that the physician consultants had conflicting opinions related to the cause of Ms. White’s respiratory deterioration. One theory the consultant considered was that Ms. White’s respiratory deterioration was possibly caused by a pulmonary embolism. In spite of this, Ms. White was never evaluated or treated for a pulmonary embolism or HIT. Although the resident was admitted with CHF, Ms. White was never adequately treated for the condition. Diuretics, a staple in CHF treatment, were discontinued – quite possibly contributing significantly to Ms. White’s declining heart function. Of further consideration was the fact that records indicated Ms. White had a probable new diagnosis of lymphocytic leukemia, which was never fully evaluated or treated. Investigation into Ms. White’s history revealed previous chest x-rays with evidence of pulmonary nodules which were never evaluated or treated. The cause of Ms. White’s death was listed as respiratory failure. As the ALN reviewer determined, the etiology of the resident’s respiratory failure was never confirmed and could have been the result of any number of conditions diagnosed after her rehabilitation stay at the defendant facility, which were not adequately evaluated or treated.

On initial review of the defendant facility records, the ALN reviewer was able to produce evidence showing the facility met the standard of care for evaluation and treatment of the respiratory symptoms Ms. White developed while a resident at the Defendant facility. The ALN reviewer’s in-depth investigation into Ms. White’s comorbid conditions and history revealed a myriad of possible sources for Ms. White’s respiratory failure and death – greatly expanding the client’s ability to argue against the facility’s liability and help mitigate possible damages.

In this case, the expertise of the ALN nurse reviewer was crucial in identifying possible contributing factors and raising questions regarding causation and mitigating factors – factors which would have gone unnoticed by a non-clinical professional. ALN Consulting’s team of nurse consultants are in a unique position to build the strongest, most manageable court case for their clients. We find the root issue by digging deeper.

ALN Consulting is a national provider of medical-legal consulting services, founded in 2002. Our expertise includes, yet is not limited to, medical malpractice, long-term care, product liability, class action/mass litigation, and toxic tort. Contact Us to put our legal nurse consulting experts on your case.

Understanding The Four Elements of Negligence

Thursday, December 3rd, 2015

Understanding the four elements of negligence are essential to evaluating a malpractice case. Since early American law was formed, negligence was considered a distinct tort in which a person was held subject to liability for carelessly causing harm to another. In order to prove negligence, a plaintiff is required to show each of the following:

- The defendant owed the plaintiff a specific duty.

- The defendant breached this duty.

- The plaintiff was harmed.

- The breach of duty caused the harm.

Some legal scholars also hold forth a fifth essential element: proximate cause, which is considered under the umbrella of the causation in the fourth element.

Negligence vs. Malpractice

The Joint Commission defines negligence as “failure to use such care as a reasonably prudent and careful person would use under similar circumstances.” Malpractice is defined as “improper or unethical conduct or unreasonable lack of skill by a holder of a professional or official position; often applied to physicians, dentists, lawyers, and public officers to denote negligent or unskillful performance of duties when professional skills are obligatory. Malpractice is a cause of action for which damages are allowed.”

Negligence is an unintentional tort, and the four elements above must be present. Malpractice goes one step further and refers to a tort committed by a professional acting in his or her professional capacity.

Professional Negligence

When a nurse or doctor is sued for malpractice, they are accused of negligence which harmed an individual in the course of his or her role as a medical professional. Defined in a nursing malpractice situation by the Black’s Law Dictionary, professional negligence is “the doing of something which a reasonably prudent person would not do, or the failure to do something which a reasonably prudent person would do, under circumstances similar to those shown by the evidence. It is the failure to use ordinary or reasonable care.”

Nursing Malpractice

The NSO, which is the largest professional liability insurance provider for nurses, has examples of nursing malpractice legal case studies and subsequent verdicts for review. They range from a Foley catheter used incorrectly which caused a urethral tear, to failure to prevent decubitus ulcers. If you are interested in reading the case studies in full, click on the following links:

http://www.nso.com/risk-education/individuals/legal-case-study/Nurse-Catheterization-for-life

References

- Stubenrauch, James M. (2007). Malpractice vs. Negligence. AJN, American Journal of Nursing, 107(7), 63-63. Retrieved from Lippincott Nursing Center database: http://www.nursingcenter.com/journalarticle?Article_ID=727909

- Owen, David G. (2007) “The Five Elements of Negligence,” Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 35: Iss. 4, Article 1. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol35/iss4/1

- Ashley, Ruth C. (2003). Understanding Negligence. Critical Care Nurse, 23(5), 72-73. Retrieved from Critical Care Nurse database: http://ccn.aacnjournals.org/content/23/5/72.full

- (2015). Legal Case Studies. Retrieved October 8, 2015, from NSO website: http://www.nso.com/risk-education/individuals/legal-case-study/Nurse-Catheterization-for-lifehttp://www.nso.com/risk-education/individuals/legal-case-study/Nurse-Decubitus-ulcer-improperly-treated

- Black HC. Black’s Law Dictionary. 9th ed. St. Paul, Minn: West Publishing Company; 1998.