Archive for the ‘LTC’ Category

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) Release New Clinical Guidelines and Taxonomy for Pressure Injuries

Friday, October 7th, 2016

In 1986, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) was formed as an independent, non-profit organization established to ensure consistent prevention, management and research of pressure ulcers. Conflicts in research and prevention created the need for this governing body, an organization that would work to create guidelines and establish best practices surrounding pressure injury wounds. NPUAP serves as the authoritative voice for improved patient outcomes in pressure ulcer prevention and treatment through the development of public policy, education and research.

Subsequent to the formation of NPUAP, the terminology to describe “pressure ulcers” was redefined and the staging system of pressure wounds expanded. Although changes were made with the intent of clarifying the differences among the stages of pressure ulcers, the new classification system led to more confusion. For example, the use of the term “injury” and “ulcer” interchangeably caused great confusion.

In April 2016, a consensus conference was convened by NPUAP to review and revise the pressure injury staging system and to standardize the terminology used to describe injury to the skin from external pressure. The term “pressure ulcer” was changed to “pressure injury.” This simple change in terminology was actually monumental, as it was a major departure from the old taxonomy in the 30 years since the panel was formed. Updates to the panel’s description of the stages of pressure injuries were developed. The group indicated that the change in terminology would more accurately describe pressure injuries to both intact and ulcerated skin.

The 2016 definition of “Pressure injury” by NPUAP describes localized damage to the skin and underlying soft tissue usually over a bony prominence, related to a medical procedure such as prolonged surgery or from a medical device. The injury can present as intact skin or an open ulcer and may be painful. The injury occurs as a result of intense and/or prolonged pressure or pressure in combination with shearing forces. The tolerance of soft tissue for pressure and shear may also be affected by microclimate, nutrition, perfusion, co-morbidities and condition of the soft tissue. Shearing occurs from friction against the skin that leads to a superficial or partial thickness injury, often resembling an abrasion.

Pressure Injury Staging

The staging system further defined pressure injuries of stages 1-4 as well as including medical device related pressure injuries and mucosal membrane pressure injuries. The following illustrations denote each stage and classification of pressure injuries.

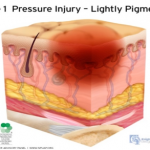

Stage 1 Pressure Injury: Non-blanchable erythema of intact skin. Intact skin with a localized area of non-blanchable erythema, which may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. Presence of blanchable erythema or changes in sensation, temperature, or firmness may precede visual changes. Color changes do not include purple of maroon discoloration; these may indicate deep pressure injury.

Stage 1 Pressure Injury: Non-blanchable erythema of intact skin. Intact skin with a localized area of non-blanchable erythema, which may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. Presence of blanchable erythema or changes in sensation, temperature, or firmness may precede visual changes. Color changes do not include purple of maroon discoloration; these may indicate deep pressure injury.

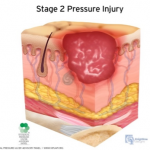

Stage 2 Pressure Injury: Partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis. The wound bed is viable, pink or red, moist, and may also present as an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Adipose (fat) is not visible nor are deeper tissues. Granulation tissue, slough and eschar are not present. These injuries commonly result from adverse microclimate and shear in the skin over the pelvis and shear in the heel. This stage should not be used to describe moisture associated skin damage (MASD) including incontinence associated dermatitis (IAD), intertriginous dermatitis (ITD), medical adhesive related skin injury (MARSI), or traumatic wounds (skin tears, burns, abrasions).

Stage 2 Pressure Injury: Partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis. The wound bed is viable, pink or red, moist, and may also present as an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Adipose (fat) is not visible nor are deeper tissues. Granulation tissue, slough and eschar are not present. These injuries commonly result from adverse microclimate and shear in the skin over the pelvis and shear in the heel. This stage should not be used to describe moisture associated skin damage (MASD) including incontinence associated dermatitis (IAD), intertriginous dermatitis (ITD), medical adhesive related skin injury (MARSI), or traumatic wounds (skin tears, burns, abrasions).

Stage 3 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin loss. Full thickness loss of skin, in which adipose tissue is visible in the ulcer, meets the definition of a Stage 3 pressure injury. Granulation tissue and epibole (rolled wound edges) are often present. Slough and/or eschar may be visible. The depth of tissue damage varies by anatomical location; areas of significant adiposity can develop deep wounds. Undermining and tunneling may occur. Fascia, muscle, tendon, ligament, cartilage and/or bone are not exposed. If slough or eschar obscures the extent of tissue loss, this becomes an Unstageable Pressure Injury.

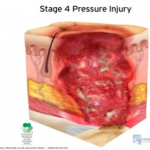

Stage 4 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin and tissue loss. Full-thickness skin and tissue loss occurs with exposed or directly palpable fascia, muscle tendon, ligament, cartilage or bone in the ulcer. Slough and/or eschar may be visible. Epibole, undermining and/or tunneling often occur. The depth of the injury varies by anatomical location. If slough or eschar obscures the extent of tissue loss, an injury such as this would be described as an Unstageable Pressure Injury.

Stage 4 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin and tissue loss. Full-thickness skin and tissue loss occurs with exposed or directly palpable fascia, muscle tendon, ligament, cartilage or bone in the ulcer. Slough and/or eschar may be visible. Epibole, undermining and/or tunneling often occur. The depth of the injury varies by anatomical location. If slough or eschar obscures the extent of tissue loss, an injury such as this would be described as an Unstageable Pressure Injury.

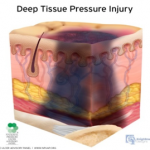

Deep Tissue Pressure Injury: persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon or purple discoloration. This type of injury may involve either intact or non-intact skin, presenting with a localized area of persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon, purple discoloration or epidermal separation revealing a dark wound bed or blood filled blister. This injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure and shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury, or may resolve without tissue loss.

Deep Tissue Pressure Injury: persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon or purple discoloration. This type of injury may involve either intact or non-intact skin, presenting with a localized area of persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon, purple discoloration or epidermal separation revealing a dark wound bed or blood filled blister. This injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure and shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury, or may resolve without tissue loss.

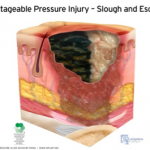

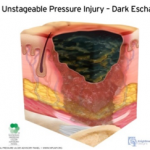

Unstageable Pressure Injury: Obscured full-thickness skin and tissue loss. This type of injury involves full-thickness skin and tissue loss. The extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar. If the slough or eschar is removed from the wound, a stage 3 or stage 4 pressure injury will be revealed. Stable eschar on the heel or ischemic limb should not be softened or removed.

Unstageable Pressure Injury: Obscured full-thickness skin and tissue loss. This type of injury involves full-thickness skin and tissue loss. The extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar. If the slough or eschar is removed from the wound, a stage 3 or stage 4 pressure injury will be revealed. Stable eschar on the heel or ischemic limb should not be softened or removed.

As classifications and guidelines change, it’s critical to have an expert on your team who understands the current definitions. ALN Consulting’s team of legal nurse consultants have their finger on the pulse of these changes, and are trained to spot inaccuracies in medical records that can effect case outcomes. Contact ALN Consulting today to learn how we can help.

Identifying Medical Malpractice Expert Witnesses

Monday, June 6th, 2016

Sometimes medical negligence is apparent without need for explanation. It doesn’t take an expert to find fault when someone operates on the wrong limb or administers the wrong medication to a nursing home resident.

If medical professionals are the only ones with control over a negative outcome, and when an adverse event could only have been caused by a medical error, our legal system invokes the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (Latin for “the thing speaks for itself.”) Simply stated, res ipsa is the principle noting that an event could have happened only due to negligence.

Although personal injury laws and rules of evidence are determined at the state level, the elements of res ipsa are pretty standard. For a case to meet the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur, three factors must be present: 1) the event would not occur in the absence of negligence; 2) the evidence of negligence rules out the possibility that the plaintiff’s actions caused the adverse event; and, 3) the negligent act occurs within the context of care provided by the defendant. It is often recommended that an expert witness be consulted, even in a case of res ipsa. The defendant’s attorney will usually challenge the notion that he or she had complete control over the circumstances.

In most cases of medical or nursing home negligence, expert witnesses are necessary to move a case forward. Lack of expert testimony can mean an early decision in an opponent’s favor – if not an outright dismissal. The facts and language of medicine are often too complex to understand. The appointed expert will walk the jury through the maze of medicine to understand why a lawsuit was filed in the first place.

Most states require plaintiffs to consult an expert witness to determine if the medical care provided to the plaintiff met the standard of care. In the legal arena, the standard of care is the level at which the average, prudent provider in a given community would practice. It is how similarly qualified practitioners would have managed the patient’s care under the same or similar circumstances. The standard of care is not necessarily the best care – just the average level expected of any care provider.

When a case does require qualified professional expertise, both plaintiffs and defendants must hire someone to serve in the role of expert witness. For cases to be tried in Federal Court, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (Fed.R. Civ.P.), requires the selected expert to prepare a detailed report in addition to a list of the expert’s prior testimony and compensation.

Although some states follow the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, others have different rules for dealing with experts. In some states, an expert witness will be deposed before trial so the opposing side can be fully prepared to counter his or her opinions. In others, like New York, a legal team is not required to disclose the name of the designated expert, but they do have to provide opposing counsel with the expert’s bibliography.

What Makes A Medical Professional An Expert?

You may ask, “What makes a medical professional an expert?” One legal dictionary defines an expert as “a person who through education or experience has developed skill or knowledge in a particular subject so that he or she may form an opinion that will assist the fact finder.”

Each state has its own definition of who may be designated as a medical expert. Some states require that professional experience must be current, either for a specified number of years or that the expert was practicing in a clinical setting at the time of the incident. A degree from an AMA or AOA-accredited medical school are common requirements, as is board certification in the experts’ area of expertise. An unrestricted medical license with no recent history of suspension or revocation is paramount. Many states mandate that potential experts must devote a certain percentage of professional time to an active clinical practice, to avoid earning the reputation as a “professional witness.”

Nurse expert witnesses typically need a B.S.N. and recent clinical expertise in the same area as the defendant, with no record of legal issues or board disciplinary actions. Certification in the expert’s nursing specialty is an added plus.

Some states adhere to different versions of a specialty rule, which requires experts to practice in the same field of medicine as the defendant physician or nurse. A state’s locality rule obligates claimants to prove, by expert testimony, the recognized standard of acceptable professional practice in the community where the defendant medical provider practices or a similar community. For example, many states require that potential expert witnesses in medical malpractice cases must come from the state in which the alleged incident occurred or from a state contiguous to the venue in which the alleged incident occurred.

In most state malpractice lawsuits, attorneys on both sides will know the witnesses’ identities before getting to trial. They will research each expert’s career from their education to their publications. Every statement in an article written or testimony in cases with similar issues will be carefully scrutinized. The legal team will research the facts on which each claim is based – gleaning all it can to uncover the weak link in an expert’s opinion.

How Can An Expert Witness Be Utilized?

Expert witnesses can be used in a variety of ways. A medical professional may appear before the court as a “fact witness.” A “fact witness” is called to explain the medicine to the judge and jury. His or her role is to provide “just the facts” about a case, with no opinion regarding the medical care provided.

In medical malpractice and nursing home litigation, causation is the common Achilles’ heel. The rub lies in two questions every medical malpractice suit must answer. First, did the defendant fail to follow the standard of care for professionals in his or her position?

To answer this, a plaintiff-appointed expert may cite medical board guidelines or publications. What would industry standards expect of the defendant? How would a conscientious colleague with the same training treat this patient? What issues would that medical professional check for, and how would those issues be treated if diagnosed? An expert witness need not practice a higher standard of care than the defendant. He or she must only be conversant enough to determine that this standard was not followed.

The second question is thornier. If there was a breach in the standard of care, did this breach cause the negative outcome or damages? Given all the factors present, how likely was the plaintiff’s injury a result of substandard care?

The plaintiff’s goal is to find an expert who believes there is evidence of a breach of the standard of care. The defense will use its own expert to establish that the standard of care was observed – or that any deviation did not directly or proximately cause the adverse event. The plaintiff’s attorney, in turn, will get to work uncovering every possible way to challenge the defense’s expert testimony.

Finding properly credentialed healthcare professionals who are willing to offer opinions is not always easy. So what’s the best way to choose an expert witness? By consulting one.

Here is where a nurse’s expertise is of particular value. Upon studying the files and medical reports, this uniquely qualified consultant can recommend appropriate specialists.

Nursing expertise is ideal in complex cases of medical and care negligence. Identifying the probable cause of a medical event takes more than simply checking blood pressure and vital signs. A nurse is interested not only in physical agility but whether the patient has followed doctors’ and therapists’ directives and asked for assistance when necessary. This expert not only researches a patient’s diet, but whether or not the patient has adhered to the diet or eaten the food provided in a hospital or care facility. He or she would review physician progress notes, consultation reports, nursing progress notes, patient teaching records, lab results for specific issues and medication history for germane clues.

Legal nurse consultants (LNCs) are generally brought in to determine the merit of a case. Some help attorneys formulate questions to be asked at a deposition or trial. Some LNCs provide both consultation and testimony, while others prefer to work “behind the scenes.”

LNCs play a vital and advantageous role finding other experts for the case – from M.D. specialists to ancillary professionals like physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and pharmacists. Nurse expert witnesses are expected to testify at a deposition and trial if needed. Unlike the LNC consulting expert, the testifying expert may or may not be required to put their opinion in writing.

Both consulting LNCs and nurse expert witnesses review medical records and deposition testimony and formulate their conclusions. They commonly organize pertinent medical records and prepare record chronologies or timelines. They may also research medical and nursing literature and standards germane to issues in the suit brought forth. Both kinds of experts offer their own unique value to legal teams – and are often hired by healthcare organizations as risk managers or compliance experts.

As with other litigation, medical malpractice and long-term care cases often pit one expert against the other. Sometimes the tipping point in a jury’s decision is how well one witness can translate technical intricacies in to language they understand. ALN Consulting’s team of nurse consultants are in a unique position to build the strongest, most manageable court case for their clients – and boil medical-legal issues down to their essence. Contact us to learn how!

CMS Interpretive Guidelines – Revision to Feeding Tube Guidance

Wednesday, March 23rd, 2016

In this installment of the ALN Consulting series on the CMS Interpretive Guidelines, we explore the most recent revisions to surveyor guidance on feeding tubes in long-term care facilities. The Interpretive Guidelines include an explanation of the intent of the law, definitions of related terms, and instructions to surveyors on how to determine compliance with the law.

The CMS Interpretive Guidelines for Nasogastric tubes updates clarify expectations for long-term facility accountability in regards to use of feeding tubes; requiring that the resident’s legal representative be properly informed, specifying how nutritional needs are monitored, and mandating that potential risks associated with feeding tubes be considered in the decision making process.

The key to a strong defense against complaints related to long-term care residents’ nutritional status, particularly those who have feeding tubes, lies in a solid understanding of these guidelines and the recent revisions.

42 C.F.R. §483.25(g) Nasogastric Tubes (F tag 322)

The CFR Regulation states, “Based on the comprehensive assessment of a resident, the facility must ensure that:

- A resident who has been able to eat enough alone or with assistance is not fed by nasogastric tube unless the resident’s clinical condition demonstrates that use of a nasogastric tube was unavoidable; and

- A resident who is fed by a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube receives the appropriate treatment and services to prevent aspiration pneumonia, diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, metabolic abnormalities, and nasal-pharyngeal ulcers and to restore, if possible, normal eating skills.”

Relevant definitions in the Interpretive Guidelines include:

Avoidable: There is not a clear indication for using a feeding tube, or there is insufficient evidence it provides a benefit that outweighs associated risks.

Unavoidable: There is a clear indication for using a feeding tube, or there is sufficient evidence it provides a benefit that outweighs associated risks.

Bolus feeding: The administration of a limited volume of enteral formula over brief periods of time.

Continuous feeding: The uninterrupted administration of enteral formula over extended periods of time.

Enteral nutrition (a.k.a. “tube feeding”): The delivery of nutrients through a feeding tube directly into the stomach, duodenum, or jejunum.

Feeding tube: A medical device used to provide enteral nutrition to a resident by bypassing oral intake.

Gastrostomy tube (“G-tube”): A tube that is placed directly into the stomach through an abdominal wall incision for administration of food, fluids, and medications. The most common type is a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube.

Jejunostomy tube (a.k.a. “percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy” (PEJ) or “J-tube”): A feeding tube placed directly into the small intestine.

Nasogastric feeding tube (“NG tube”): A tube that is passed through the nose and down through the nasopharynx and esophagus into the stomach.

Transgastric jejunal feeding tube (“G-J tube”): A feeding tube that is placed through the stomach into the jejunum and that has dual ports to access both the stomach and the small intestine.

Tube feeding (a.k.a. “enteral feeding”): The delivery of nutrients through a feeding tube directly into the stomach, duodenum, or jejunum.

Regulation Tag F 322

The feeding tube requirement has two parts. The first aspect requires that the facility utilize a feeding tube only after it determines that a resident’s clinical condition demonstrates this intervention was unavoidable. The second aspect requires that the facility provides to the resident who is fed by a tube services to prevent complications, to the extent possible, and services to restore normal eating skills, if possible.

The facility is in compliance with 42 CFR §483.25(g), if staff:

- Uses a feeding tube to provide nutrition and hydration only when the resident’s clinical condition makes this intervention necessary based on adequate assessment, and after other efforts to maintain or improve the resident’s nutritional status have failed;

- Manages all aspects of a feeding tube and enteral feeding consistent with current clinical standards of practice in order to meet the resident’s nutritional and hydration needs and prevent complications; and

- Identifies and addresses the potential risks and/or complications associated with feeding tubes, and provide treatment and services to restore, if possible, adequate oral intake.

Surveyor “Probes” in Facility Use of Feeding Tubes

Probes, or questions posed by the Interpretive Guidelines for surveyors, can be used by the defense team to bolster evidence that a practitioner or facility met the standard of care. There are many probes in F tag 322 related to resident rights; technical and nutritional aspects of feeding tubes; care of the feeding tube; and complications related to the feeding tube and/or the enteral nutrition product. Some examples of surveyor probes include:

- Was the resident and/or the resident’s legal representative informed about the relevant benefits and risks of tube feeding?

- How has the staff and practitioner determined the cause of decreased oral intake/weight loss or impaired nutrition and attempted to maintain oral intake prior to the insertion of a feeding tube?

- How did the staff determine the resident’s nutritional status was being met, such as periodically weighing the resident, and how did they decide whether the tube feeding was adequate to maintain acceptable nutrition parameters?

- How has the facility identified the resident at risk for impaired nutrition, identified and addressed causes of impaired nutrition, and determined that use of a feeding tube was unavoidable?

- How has the staff verified that the feeding tube was properly placed?

- How has the staff monitored a resident for possible complications (e.g., diarrhea, nutritional deficits, aspiration, depression, withdrawal, etc.) related to a feeding tube and the tube feeding, and how have they identified and addressed such complications?

Updates to the Interpretive Guidelines

The Interpretive Guidelines entitled Nasogastric tubes was vastly updated in November 2014. For the purpose of the guidelines, the regulatory title is considered to include any feeding tube used to provide enteral nutrition to a resident by bypassing oral intake. (Since the regulation was created use of actual nasogastric tubes have become rare, and use of other types of enteral feeding tubes have become more prominent.)

The newest guidance stresses the unavoidability standard, and also emphasizes quality of life and resident choice. Based on the guidelines, it could be argued that some examples of possible adverse effects from feeding tubes such as diminished socialization and loss of the experience of taste, texture, and chewing must be considered as important, and may possibly outweigh the benefits of feeding tubes such as preventing malnutrition and dehydration, and aiding wound healing. A new statement regarding the use of feeding tubes in elderly patients with dementia also addressed the controversy in this arena. “The literature regarding enteral feeding of these individuals suggests that there is little evidence that enteral feeding improves clinical outcomes (e.g., prevents aspiration or reduces mortality).”3

In the defense of the use, non-use, or complications of feeding tubes, the Interpretive Guidelines; Nasogastric tubes now provide a much larger framework for the difficult end of life decisions which are inherent in turning towards non-oral sustenance. With the comprehensive updates added to this guideline, ALN Consulting can help your defense team pinpoint crucial, relevant prompts and research to strengthen a case with complaints involving tube feeding.

References

- Harris, Rick E. (2015). How to Use the CMS Surveyor Guidance to Craft a Winning Defense [Presentation at the DRI LTC/SNF Seminar].

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2015). State Operations Manual – Appendix PP – Guidance to Surveyors for Long-term Care Facilities. Retrieved 02/23/16.

- Compliance Solutions for the Perfect Survey Every Day. (2014). F322. Retrieved 02/23/16 from The Perfect Survey website.

CMS 5 Star Ratings of Nursing Homes

Wednesday, March 23rd, 2016

For the past several months, you may have been following along with our CMS (Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services) Interpretive Guidelines series. In this installment, Devin Shelby, Administrator of Dickson Health and Rehabilitation, discusses the change in CMS nursing home rating procedures, most notably shifting the reviews to monthly from annually.

The CMS 5-Star Rating is the only standard measuring tool for nursing homes available to the public. It is comprised of 3 sections which include measurements of regulatory inspections, clinical quality and staffing. Facilities are rated from 1 to 5 Stars on each section, with a composite score for the overall rating. The public relies heavily on this tool when evaluating nursing homes. The tool has some significant shortcomings, most notably regarding staffing measurements:

- Staffing measurements for the 5 Star Program are taken from a single two-week period prior to a facility’s annual inspection.

- The resulting snapshot measurement is reported as the facility’s Staffing Star Rating for the entire next year.

- Staffing in a nursing home can vary greatly over relatively short intervals, much less an entire year. This two-week snapshot is likely not indicative of the facility’s actual staffing throughout the year.

- In some areas, there are up to 2 years between annual inspections, therefore staffing ratings could be up to two years old.

- This can give the public a very inaccurate indication of actual staffing levels at any point in time, over a very long time.

- Compounding this, if a facility receives a 1 Star rating in any of the 3 categories, such as staffing, the facility’s OVERALL Star Rating is automatically reduced by 1 Star for the ENTIRE year, or until the next “annual” inspection.

To summarize, this two week snapshot measurement often gives the public an inaccurate picture of a nursing facility’s actual staffing.

For more detail in reference to a significant change in the reporting intervals for facilities going forward, read this article. Starting in July 2016 facilities will report staffing on a monthly basis. This much shorter reporting interval will allow the public to have more accurate, almost real-time, staffing data for facilities they wish to evaluate. It will be a bit of a burden for facilities to report so often, but it beats the alternative of having potentially financially devastating and inaccurate staffing numbers posted on a public notice for an extended period of time.

Contact ALN Consulting with any questions regarding how this change may impact your case, or to better understand these guideline revisions.

The Power of a Nurse’s Words

Wednesday, March 23rd, 2016

We here at ALN sometimes encounter a sense of “Am I making a difference and is it enough?” in our profession. And it’s interesting to hear that same thing from other nurses. Diane M Goodman recently posted a piece that so compelled us, we just had to share. Thank you, Diane.”

Sticks and Stones; The Power of a Nurse’s Words

By Diane M. Goodman, Originally appeared in MedScape, Jan 21, 2016

Many of us were raised in a generation by mothers who warned us of the old English adage about taunting others through the use of name-calling and words. We knew better. Words could either be unbelievably comforting or leave lasting scars on our memories.

As nurses, our words and our voices are no less profound. We can change the trajectory of a life by coaxing change from a desultory or despondent patient, and we can inspire peers to greatness when they feel they cannot work another moment or another busy day.

Sharing research with peers may allow them to comprehend the improbability of what we DO on a daily basis. By reading a quantitative time-study, for example, and sharing it with colleagues, they may have an improved understanding of why nurses need stress management techniques to perform their jobs. Nursing is extremely difficult work. Expecting substantive conversation or specific phrases to “just happen” at the bedside is like asking the typical pilot to land an airplane on the Hudson!

Nurses, on the average, complete >70 (!!) tasks per hour. Nurses change tasks approximately every 55 seconds. They are also interrupted approximately once every 32 minutes, with the highest amount of interruptions recorded during medication administration!*

Why is it important to know this? While this time/event study was conducted in Sydney, the research was rigorous enough to be utilized internationally as an example of why nurses may find it “difficult” to bond with patients. We may be groping to find the right words to instill initiative, hope, and change in our patients. We could even be struggling a bit.

Nina (not her real name) reminded me of this in ICU. I was struggling. She was paralyzed, intubated, ventilated, and so, so sick. I was sure she would not survive. She was only 19.

I was exhausted every night, hanging more blood, platelets and medications than I had ever hung in my life. She was septic and she had leukemia. “Sticks and stones”, I repeated in my head over and over, warning myself not to frown or sigh, or show tiredness EVER. Instead, I stroked her hair, and told her how much I loved my little sister, and my dogs. I played music for her when my voice got tired or I ran out of words. If nothing sweet or positive was left to be said, I smiled and hummed, night after exhausting night. OK, so I did a lot of humming.

Her bed was empty one night, as ICU beds often are. Rehab, they said. Long-term. Newer, sicker patients came and went.

Six months later, a young, attractive woman was wheeled in with a huge family circling her, including one very determined sister. It was Nina. She remembered nothing of her stay but a woman who stroked her hair and hummed and talked softly of dogs and family. I would have given her almost zero odds of surviving, and here she was!! Sitting tall, with very little residual effects. I couldn’t believe she remembered me! She remembered nothing else.

Interpretive Guidelines for Long-Term Care Facilities in Litigation

Thursday, December 17th, 2015

When defending cases against long-term care facilities, the Interpretive Guidelines become the canon by which the operations of a facility are judged. Like most law, long-term care regulations must be scrutinized through interpretation. Understanding the background and application of the Interpretive Guidelines can help build solid claims for litigation. As part of ALN Consulting’s commitment to our legal partners, we explain the Interpretive Guidelines and outline the importance of their application to strengthen your legal team’s expertise.

How are Nursing Homes regulated?

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA ’87) and the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA ’97) require the Federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to create regulations that govern practices in long-term care and skilled nursing facilities. The regulations resulting from OBRA and BBA are divided into two parts.

First, the regulations are stated in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) and referred to as “F-tags.” The second part of the regulation requires the agency responsible for enforcing the regulation to derive the Interpretive Guidelines. The Interpretive Guidelines should include an explanation of the intent of the law, definition of terms, and instructions on determining compliance with the law.

Who are the surveyors and how are the Interpretive Guidelines used?

Long-term care facilities receiving Medicare or Medicaid funds must be surveyed approximately once a year, and no less than 15 months. In almost all cases, these surveys are performed by state employees who use federal regulations to inspect facilities. Since the surveys are performed by state employees, the Interpretive Guidelines can be found in the State Operations Manual (SOM). The SOM provides guidance to each state on all aspects of state health care operations. Appendix PP to the SOM applies to long-term care and skilled nursing facility surveys.

Since Interpretive Guidelines are not included in the CFR, they do not have the force of law. However, they are still considered definitive by the CMS regarding what each regulation means. While not as authoritative as “standard of care,” the Interpretive Guidelines have a tremendous bearing on a long-term care liability case. The Interpretive Guidelines are designed to assist surveyors in understanding the CFR requirements, applying those requirements consistently, and suggesting pathways for inquiry. The CMS continually produces revisions of the Interpretive Guidelines for surveyors’ use in nursing homes. State and federal surveys use the newest improvements that are backed by evidence.

Examples of Interpretive Guidelines

Appendix PP of the SOM covers long-term care operations and lists each CFR “F-tag,” followed by the Interpretive Guidelines, which include definitions of terms and questions for the surveyors to consider during the survey. For example, let’s examine a short Interpretive Guideline for dietary personnel staffing:

F362

483.35 (b) Standard Sufficient Staff

- The facility must employ sufficient support personnel competent to carry out the functions of the dietary service

Interpretive Guidelines: §483.35(b)

“Sufficient support personnel” is defined as enough staff to prepare and serve palatable, attractive, nutritionally adequate meals at proper temperatures and appropriate times and support proper sanitary techniques being utilized.

Procedures: §483.35(b)

For residents who have been triggered for a dining review, do they report that meals are palatable, attractive, served at the proper temperatures and at appropriate times?

Probes: §483.35(b)

- Sufficient staff preparation: Is food prepared in scheduled timeframes in accordance with established professional practices?

- Observe food service: Does food leave kitchen in scheduled timeframes? Is food served to residents in scheduled timeframes?

Standing alone, the CFR statement could be interpreted differently by individual surveyors of different states and personal experiences. However, the Interpretive Guideline provides concrete questions for the surveyor to determine if the federal regulation has been met.

Types of Surveys – Implementation of Interpretive Guidelines

In addition to annual surveys, nursing homes receiving Medicare or Medicaid funds are also subject to complaint surveys at any time the state survey agency or the CMS chooses. An annual or complaint survey can result in federal citations against the facility, which require the nursing home to create a plan of correction and submit it to the survey agency. The survey agency then verifies the correction, usually by revisiting the nursing home. These follow up visits can also result in additional citations.

Each problem, or deficiency, found is given a rating for “severity” and “scope,” or an “s/s” score on a scale of A to L, the latter of which is the most severe. For instance, a facility has a complaint survey based on a resident’s fall-induced fracture. The surveyor finds failure to ensure adequate supervision in order to prevent accidents, and rates the “s/s” as “G,” (defined as fairly severe) since the resident sustained a fractured hip. The facility submits a plan to correct the deficiency and the facility is re-surveyed a month later. The follow-up survey justifies removal of the immediate jeopardy, but the facility is not in full compliance due to a failure to complete the quality assurance related to staff monitoring, analysis of monitoring results, and a development and implementation of their plan. The facility is re-surveyed two weeks later and found to be in complete compliance.

Sanctions can be imposed on nursing homes that fail to meet requirements. State imposed sanctions can include citations and fines, bans on admission, and appointment of temporary managers. The facility’s license can also be suspended or revoked. If a nursing home is certified under CMS, federal sanctions can include directed plans of correction, directed in-service trainings, state monitoring, and/or denial of payment for new admissions, civil fines, and termination of Medicare or Medicaid payments. All nursing homes federally regulated under the CMS are listed under datasets created by the CMS called the “Five Star Nursing Home Quality Rating System.”

How to use Interpretive Guidelines in Nursing Home Litigation

Litigators defending long-term care and skilled nursing facilities can use CMS’s guidance to surveyors to help strengthen their arguments against liability. Consulting the Interpretive Guidelines could demonstrate that a facility intervened with numerous, appropriate interventions, in accordance with the guideline(s), but still received a poor outcome. Using a facility’s compliance with the Interpretive Guidelines could strengthen the claim that the outcome was likely unavoidable. In many cases, plaintiffs attempt to use the regulations and survey results to make “standard of care” arguments and sweeping claims against the care rendered by nursing home staff in a particular case, making it imperative to understand the basis of their argument.

Applying the Interpretive Guidelines in order to strengthen a claim requires expert knowledge and time-consuming research. With more than 127 collective years of legal experience and familiarity with the CMS Interpretive Guidelines, ALN’s nurse consultants serve as a unique partner for legal teams in nursing home litigation. Utilizing legal nurse consultants familiar with the CMS Interpretive Guidelines and skilled in survey analysis will help bolster the defense team’s understanding of these issues in the case and improve the defensibility of the claim.

References

- Harris, Rick E. (2015). How to Use the CMS Surveyor Guidance to Craft a Winning Defense [Presentation at the DRI LTC/SNF Seminar].

- Thomas, David R. (2006). The New F-tag 314: Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers. In Clinical Practice in Long Term Care (pp523-524). St. Louis, MO: AMDA.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2015). State Operations Manual – Appendix PP – Guidance to Surveyors for Long Term Care Facilities. Retrieved 11/20/15

Prevention and Policy: Falls in Long Term Care

Thursday, December 10th, 2015

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined falls in the 2007 Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age as, “inadvertently coming to rest on the ground, floor or other lower level, excluding intentional change in position to rest in furniture, wall or other objects.” The definition of falls does not include injury because not all falls cause injury. In fact, the CDC reports that one out of three older people fall each year, but less than half tell their doctor. Falling once doubles the chance of another fall. Insurance carrier actuarial analysis from 2014 showed that long term care liability claims are rising 3% annually, and falls are the most frequent allegation from skilled nursing facilities. On average, the claims had total payments of $131,104-171,960. Beyond consideration of the monetary losses of the facility, falls also have a major impact both physically and psychologically on those injured. Furthermore, the CDC reports that there were 25,464 deaths in 2013 from unintentional falls in the over 65 population in the United States, and falls are the most common cause of hip fractures and traumatic brain injuries. Falls should be among a long term care facility’s top priorities in terms of prevention and policy review.

The dichotomy which exists in long term care fall prevention is in the value placed on quality of life and autonomy where possible, and treatment goals to maximize mobility and minimize restraint. Long term facilities exist not just to prevent injury, but also provide a home for the resident, where the staff attempts to balance safety and precaution with the desires and autonomy of the resident. Janice Morse RN, PhD, the creator of a well-known fall risk assessment tool, the “Morse Fall Scale,” acknowledged as far back as 1987 that not all falls are preventable, and grouped falls into three types: physiological anticipated, physiological unanticipated, and accidental falls. Morse felt that even though some falls may not be preventable, the goal of the interdisciplinary team should still be to do all they could in prevention, and many of the risk strategies that she and her team published in 1987 still stand today as the standard of fall prevention care.

Risk Assessment

While there are many fall risk assessment and screening tools used throughout the U.S., three tools have been validated in multiple studies: The St. Thomas’ Risk Assessment Tool in Falling Elderly Inpatients (STRATIFY), the Morse Falls Scale, and the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model. It is the standard of care to assess a resident for risk of falls upon admission, and re-evaluate risk upon change in resident condition. Issues which can raise a resident’s risk of falling include:

- History of falls.

- Medications (anti-cholinergics, anti-epileptics, antipsychotics, anti-hypertensives, antihistamines, benzodiazepines, sedative hypnotics, and recent changes in medication regimens).

- Co-morbidities such as osteoporosis, incontinence, cardiovascular disease, and pain.

- Vision changes.

- Decreased strength and mobility.

- Activity of Daily Living (ADL) assistance needs.

- Diabetes (blood sugar irregularities, peripheral neuropathy).

It seems the more of these risk factors a resident has, the more synergistic the risk factors become causing a much higher risk of falls in residents with multiple risk factors. In addition to the skilled nursing facility staff assessing the resident’s risk, the family should be involved in ensuring they have a clear picture of the resident’s health and have realistic expectations of the risks involved if their loved one does not comply with using the call bell and other preventative measures instituted. Keeping the family informed and part of the planning process many times contributes positively to the outcome should a fall occur.

Prevention

It is not enough to merely identify risk. Once risk has been assessed, resident specific interventions should be identified and implemented. Each resident should have a plan of care which addresses falls and injury risk. Dr. Craig Wilson, in a recent presentation on Fall Prevention, recommended the following universal fall reduction strategies (instituted regardless of fall risk) for all residents:

- Orient new residents to the environment, and instruct residents on the proper use of the nurse call system, ensuring they are operational and accessible for all residents.

- Position important items such as call light, water, and telephone within reach.

- Maintain an obstruction/spill-free environment.

- Remove all electrical cords from traffic areas.

- Place the bed in the lowest position with brakes locked.

- Use non-skid socks or footwear when out of bed.

- Utilize nightlights during evening shifts.

- Reassess ambulation status daily.

- Note and report changes in physical and mental status promptly.

- Never leave a resident unattended in the bathroom.

According to geriatric falls expert Elizabeth Hill, RN, PhD, studies have shown that individuals are at greater risk of falling when they are in the process of performing purposeful actions such as reaching for an object or using the toilet. Therefore, some of the most important interventions your facility can incorporate is the proper use of assistive devices such as grabbers and shoe horns, and hourly rounding. Hourly rounding is not the standard, most long term facilities check on residents at least every two hours, but rounding more often can eliminate many of the falls associated with non-compliance with the call system. Ms. Hill describes the “4 P’s” included in a nursing staff check, which include: Pain, Potty, Positioning, and Possessions.

Other important prevention categories include monitoring devices, such as bed alarms and surveillance, bed rails use to the extent that it assists residents with bed mobility but does not restrain free movement, keeping the bed in a locked and low position, and use of floor mats, larger mattresses, and hip protectors. Use of the interdisciplinary team beyond nursing, such as CNA’s, Occupational Therapy, Physical Therapy, Pharmacists, and Podiatrists can cover many of the reassessment points needed for a comprehensive plan that is continually updated based on resident condition and changes.

Response to Falls to Improve Outcomes and Minimize Risk

Let’s say your facility had a comprehensive and accurate assessment of a new resident, and created and implemented a care plan that was felt to be complete by the entire interdisciplinary team, and yet the resident still sustained a fall with possible injury. What are the immediate important steps for your staff to take? The first steps should focus on the resident’s safety:

- Evaluate level of consciousness and vital signs.

- Ask the resident if there is any neck or back pain, and assess pain all over the body.

- Check the skin for bruising, or injury.

- Notify the doctor, supervisor, and family (the doctor should always be notified before the family and documented as such). Determine with the physician if the resident needs to be transferred to the ED for further evaluation and treatment.

- If the resident stays in the facility, monitor neurological checks for at least 24 hours for unwitnessed falls.

All of the immediate steps should be documented comprehensively, and actions should be timely and documented as such.

Once the resident’s immediate safety is addressed and documented, and all appropriate actions are taken, an investigation should be done. A root cause analysis should be performed, and all plans should be reassessed and tailored to the resident’s new status. If the resident sustained a reportable injury it should be communicated to the State Board of Health. The family should be involved in new strategies for falls prevention.

Policy and Prevention of Litigation

Above all, a facility must have a falls policy in place that is frequently reviewed and updated. New staff should have a set training program for education regarding falls, and each unintentional fall should have a pathway for treatment and documentation that is practiced. The implementation of a “Falls Team” or IDT who reviews each fall, performs root cause analysis, and ensures implementation of new interventions for prevention is not a “standard of care” per se, but is a best practice and can decrease risk in your facility. Should you find your facility in the unfortunate position of defending a fall/injury case, a legal nurse consultant will help the legal team identify strengths and weaknesses in the assessment, prevention, and treatment rendered. If your facility and all its staff are committed to keeping falls from occurring in the long term setting, and continually work to implement interventions based on the residents’ current condition, you will have a low risk of litigation from falls and injury.

References

1. World Health Organization. (2007). WHO Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age. Retrieved October 16, 2015 from the World Health Organization website: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf

2. Aon 2014 Long Term Care Liability Actuarial Analysis. http://www.phca.org/docs/Aon_2014_Long_Term_Care_Liability_Actuarial_Analysis_full.pdf.

3. AON 2011 General Liability and Professional Liability Actuarial Analysis. http://www.aon.com/risk-services/thoughtleadership/reports-pubs_2011_long_term_care_survey.jsp

4. CNA Aging Services Report 2012 https://www.cna.com/vcm_content/CNA/internet/Static%20File%20for%20 Download/Risk%20Control/Medical%20Services/AgingServices2012DataAnalysis-SupportingtheNeedforIndustryChange-10-2012.pdf.

5. Falls among Older Adults: An Overview. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/Falls/adultfalls.html.

6. MMWR QuickStats: Death Rates* from Unintentional Falls† Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years, by Sex — United States, 2000–2013. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6416a12.htm.

7. Morse, J.M., Tylko, S.J., & Dixon, H.A. (1987). Characteristics of the fall-prone patient. Gerontologist, 27(4), 516-522.

8. Oliver D et al. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997 Oct 25; 315(7115):1049-53.

9. Morse JM et al. A prospective study to identify the fall-prone patient. Soc Sci Med. 1989; 28(1):81-6.

10. Hendrich AL et al. Validation of the Hendrich II Fall Risk Model: a large concurrent case/control study of hospitalized patients. Appl Nurs Res. 2003 Feb; 16(1):9-21.

11. Meade, C.M., Bursell, A.L., & Ketelson, L. (2006). Effects of nursing rounds: on patients’ call light use, satisfaction, and safety. American Journal of Nursing, 106(9), 58-70.

12. Bloom, A.S. (2015). Back to Basics: Falls, Wounds, Infection and Death. [DRI Presentation].

13. Wilson, C.J. (2015). Don’t Get Tripped Up: State of the Art Fall Prevention. [DRI Presentation].

14. Hill, Elizabeth (2015). The Latest in Falls and Fall Prevention. [DRI Presentation].

Understanding The Four Elements of Negligence

Thursday, December 3rd, 2015

Understanding the four elements of negligence are essential to evaluating a malpractice case. Since early American law was formed, negligence was considered a distinct tort in which a person was held subject to liability for carelessly causing harm to another. In order to prove negligence, a plaintiff is required to show each of the following:

- The defendant owed the plaintiff a specific duty.

- The defendant breached this duty.

- The plaintiff was harmed.

- The breach of duty caused the harm.

Some legal scholars also hold forth a fifth essential element: proximate cause, which is considered under the umbrella of the causation in the fourth element.

Negligence vs. Malpractice

The Joint Commission defines negligence as “failure to use such care as a reasonably prudent and careful person would use under similar circumstances.” Malpractice is defined as “improper or unethical conduct or unreasonable lack of skill by a holder of a professional or official position; often applied to physicians, dentists, lawyers, and public officers to denote negligent or unskillful performance of duties when professional skills are obligatory. Malpractice is a cause of action for which damages are allowed.”

Negligence is an unintentional tort, and the four elements above must be present. Malpractice goes one step further and refers to a tort committed by a professional acting in his or her professional capacity.

Professional Negligence

When a nurse or doctor is sued for malpractice, they are accused of negligence which harmed an individual in the course of his or her role as a medical professional. Defined in a nursing malpractice situation by the Black’s Law Dictionary, professional negligence is “the doing of something which a reasonably prudent person would not do, or the failure to do something which a reasonably prudent person would do, under circumstances similar to those shown by the evidence. It is the failure to use ordinary or reasonable care.”

Nursing Malpractice

The NSO, which is the largest professional liability insurance provider for nurses, has examples of nursing malpractice legal case studies and subsequent verdicts for review. They range from a Foley catheter used incorrectly which caused a urethral tear, to failure to prevent decubitus ulcers. If you are interested in reading the case studies in full, click on the following links:

http://www.nso.com/risk-education/individuals/legal-case-study/Nurse-Catheterization-for-life

References

- Stubenrauch, James M. (2007). Malpractice vs. Negligence. AJN, American Journal of Nursing, 107(7), 63-63. Retrieved from Lippincott Nursing Center database: http://www.nursingcenter.com/journalarticle?Article_ID=727909

- Owen, David G. (2007) “The Five Elements of Negligence,” Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 35: Iss. 4, Article 1. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol35/iss4/1

- Ashley, Ruth C. (2003). Understanding Negligence. Critical Care Nurse, 23(5), 72-73. Retrieved from Critical Care Nurse database: http://ccn.aacnjournals.org/content/23/5/72.full

- (2015). Legal Case Studies. Retrieved October 8, 2015, from NSO website: http://www.nso.com/risk-education/individuals/legal-case-study/Nurse-Catheterization-for-lifehttp://www.nso.com/risk-education/individuals/legal-case-study/Nurse-Decubitus-ulcer-improperly-treated

- Black HC. Black’s Law Dictionary. 9th ed. St. Paul, Minn: West Publishing Company; 1998.

Call to Action – Reform of Requirements for Long Term Care Facilities

Thursday, September 3rd, 2015

The requirements for Long-Term Care (LTC) facilities are the health and safety standards that LTC facilities must meet in order to participate in the Medicare and Medicare programs. Found at 42 CFR 483 Subpart B, these requirements have not been comprehensively updated since 1991 despite considerable changes in the industry. The proposed changes, according to CMS, “are necessary to reflect the substantial advances that have been made over the past several years in the theory and practice of service delivery and safety.”

Many of the provisions are substantial and will significantly affect the day-to-day operations of close to 15,700 certified SNFs and NFs. With so many new requirements proposed at one time, along with the reorganization of existing regulations, reasonable concerns are surfacing from organizations such as the American Health Care Association. Over what period of time will the changes be phased in? How will the additional staff resources needed be paid for? Will this take resources away from caring for residents? In the upcoming months, we will be working with our clients to understand the proposed changes and helping develop strategies for preparedness. In the meantime, we encourage you to submit your concerns and comments on the proposed rule directly to CMS. To be assured consideration, comments must be received no later than 11:59 p.m. on September 14, 2015

To view the proposed rule, please visit:

http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-07-16/pdf/2015-17207.pdf

To submit a comment, visit the following and click on “Comment Now”.

http://www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=CMS-2015-0083-0001

Courtesy of Rebecca Adelman, founding shareholder of Hagwood Adelman Tipton PC, the following is a summation of the proposed changes.

Definitions (§483.5):

- Adds definitions for “adverse event”; “documentation”; “posting/displaying”; “resident representative” “abuse”; “sexual abuse”; “neglect”; “exploitation”; “misappropriation of resident property”; and “person centered care”.

- Resident rights (§483.10):

- CMS would retain all existing residents’ rights, but update language and organization to include, e.g., electronic communications. Proposed revisions would:

- Eliminate language, such as “interested family member”; replace “legal representative” with “resident representative.”

- Address roommate choice.

- Add language regarding physician credentialing to specify that the physician chosen by the resident must be licensed to practice medicine in the state where the resident resides, and must meet professional credentialing requirements of the facility.

- New Section: Facility responsibilities (§483.11)

- Focuses on facility responsibilities (protecting the residents’ rights, enhancing quality of life). This section parallels many residents’ rights provisions.

- Visitation: Would establish open visitation, similar to the hospital conditions of participation (CoPs).

- Abuse/Neglect/Exploitation (§483.12): Would revise “Resident behavior and facility practices,” to “Freedom from abuse, neglect, and exploitation”; and

- Prohibit employment of individuals with disciplinary actions against their professional license by a state licensure body following a finding of abuse, neglect, mistreatment, or misappropriation of property.

- Require implementation of written policies and procedures that prohibit and prevent abuse, neglect, mistreatment and/or misappropriation of property.

- Transitions of Care (§483.15): Revises “admission, transfer and discharge rights,” to apply to all transfers of resident care.

- Transfers / Discharge: Would require specific information/data elements, e.g., demographic; history of present illness including, e.g., active diagnoses, functional status, medications; reason for transfer and past medical/surgical history, be exchanged with the receiving provider. CMS is not proposing a specific form, format, or methodology.

- Resident assessments (§483.20); Preadmission Screening and Resident Review (PASRR): Would clarify appropriate coordination of resident assessment with PASRR.

- Would add exceptions to PASRR requirements for mental illness and intellectual disabilities for admission with respect to transfers to or from a hospital.

- Would require notification of state mental health or intellectual disability authorities promptly after a significant change in the mental or physical condition of a resident with a mental illness or intellectual disability.

- New Section: Comprehensive Person-Centered Care Planning (§483.21) – Would require development of a baseline care plan for each resident within 48 hours of admission, including instructions needed to provide effective and person-centered care meeting professional standards.

- PASRR: Would require the care plan to include any specialized services or specialized rehabilitation services the facility will provide as a result of PASRR; a rationale for disagreement with PASRR findings must be documented in the medical record.

- Interdisciplinary Team (IDT): Would add a nurse aide, food and nutrition services, and a social worker to the IDT that develops the comprehensive care plan.

- Would require written explanation in the medical record if participation of the resident and their resident representative is determined not practicable.

- Discharge Planning [as part of Comprehensive Person-Centered Care Planning]: Would implement IMPACT Act requirements for long term care facilities to take into account quality, resource use, and other measures to inform and assist the discharge planning process, while accounting for resident treatment preferences and goals.

- Would require facilities to document the resident’s goals for admission in the care plan; assess potential for future discharge; include discharge planning in the comprehensive care plan, as appropriate.

- Would require the discharge summary to include reconciliation of all discharge medications with pre-admission medications (prescribed and OTC).

- Would require addition to the post discharge care plan a summary of arrangements made for follow up and any post discharge services.

- Quality of care and Quality of Life (§483.25) [retitled] – Would clarify that quality of care and quality of life are overarching principles in all care and services.

- Would clarify the requirements regarding a resident’s ability to perform ADLs.

- No proposal, but CMS is seeking comments on whether current requirements for activities’ director are appropriate; what minimum requirements should be.

- Would modify requirements for nasogastric tubes to reflect current clinical practice, and include enteral fluids in requirements for assisted nutrition and hydration.

- Would add a new requirement that facilities ensure pain management needs are met

- Would move current provisions for unnecessary drugs, antipsychotics, medication errors, and influenza and pneumococcal immunizations to Pharmacy services.

- Physician Services

- Would require an in-person evaluation by a physician, a physician assistant (PA), nurse practitioner (NP, or clinical nurse specialist (CNS) before an unscheduled transfer to a hospital.

- Would allow physicians to delegate dietary orders to dietitians and therapy orders to therapists.

- Nurse Staffing – Would add a competencies/skill set requirement for determining sufficient nursing and direct care staff based on a facility assessment, including but not limited to: # of residents, acuity, range of diagnoses, and care plan content.

- New Section: Behavioral health services (§483.40) – Would focus on provision of necessary behavioral health care and services to residents in accordance with their comprehensive assessment and plan of care.

- Would require staff to have appropriate competencies to provide behavioral health care and services, including care of residents with mental and psychosocial illnesses and implementing non-pharmacological interventions.

- CMS notes in the Preamble that reference to mental health/illness includes substance abuse disorders.

- Would add “gerontology” bachelor’s degree to the minimum social worker educational requirements.

- Would require staff to have appropriate competencies to provide behavioral health care and services, including care of residents with mental and psychosocial illnesses and implementing non-pharmacological interventions.

- Pharmacy services (§483.45); Drug Regimen Review

- Would require pharmacist review of a resident’s medical chart at least every 6 months and when the resident is new to the facility, a resident returns or is transferred from a hospital or other facility, and during each monthly DRR when a resident has been prescribed or is taking a psychotropic drug, an antibiotic or any drug the QAA Committee has requested be included in the monthly drug review.

- Would require the pharmacist to document any irregularities noted during the DRR, including at minimum, the resident’s name, the relevant drug and irregularity identified, to be sent to the attending physician, medical director, and director of nursing.

- Would require the attending physician to document that he/she has reviewed the identified irregularity and what, if any, action they have taken. “Irregularities” would include “unnecessary drugs.”

- Would require facilities to ensure residents who have not used psychotropic drugs not be given these drugs unless medically necessary; receive gradual dose reductions and behavioral interventions unless clinically contraindicated.

- “Psychotropic drug” would include any drug that affects brain activities associated with mental processes and behavior.

- PRN orders for psychotropic drugs would be limited to 48 hours unless the primary care provider reviews and documents the rationale.

- New Section: Laboratory, radiology, and other diagnostic services (§483.50)

- Would clarify that a PA, NP, or CNS may order laboratory, radiology, and other diagnostic services in accordance with state and scope of practice laws.

- Would clarify that the ordering practitioner be notified of abnormal laboratory results when they fall outside of clinical reference ranges, in accordance with facility notification policies and procedures.

- Dental services (§483.55)

- Would prohibit SNFs from charging a Medicare resident for the loss or damage of dentures determined to be the facility’s responsibility.

- Would require NFs to assist eligible residents to apply for reimbursement of dental services under the Medicaid state plan.

- Would clarify that a referral for lost or damaged dentures “promptly” means within 3 business days absent documentation of any extenuating circumstances.

- Dietary Services

- Would require facilities to employ sufficient staff with appropriate competencies to carry out dietary services in accordance with resident assessments, individual care plans, and facility census.

- A “qualified dietitian” is registered by the Commission on Dietetic Registration of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics or meets state licensure or certification requirements. Dietitians hired/contracted with prior to these regulations, would have 5 years to meet the new requirements.

- The director of food and nutrition service must be a certified dietary manager, certified food service manager, or be certified for food service management and safety by a national certifying body or have an associate’s or higher degree in food service management or hospitality; would have to meet any state requirements for food service managers.

- Would require menus to reflect religious, cultural and ethnic needs and preferences, be updated periodically, and reviewed by the qualified dietitian or other clinically qualified nutrition professional for nutritional adequacy while not limiting residents’ right to personal dietary choices.

- Would require facilities to consider resident allergies, intolerances, and preferences and ensure adequate hydration.

- Would allow attending physicians to delegate prescribing resident diets to registered or licensed dietitians, including therapeutic diets, in accordance with state law.

- Would require availability of suitable, nourishing alternative meals and snacks for residents who want to eat at non-traditional times or outside of scheduled meal times in accordance with the plan of care.

- Would require documentation in the care plan the clinical need for a feeding assistant and the extent of dining assistance needed.

- Would clarify facilities may procure food items directly from local producers and may use produce grown in facility gardens.

- Would clarify residents are not prohibited from consuming foods not procured by the facility.

- Would require a policy regarding use and storage of foods brought to residents by family and other visitors.

- Specialized rehabilitative services (§483.65)

- Would add respiratory services to specialized rehabilitative services.

- Would clarify what constitutes rehabilitative services for mental illness and intellectual disability.

- Would establish new health and safety standards for provision of outpatient rehabilitative therapy services.

- Facility Assessment – would require facilities to conduct, document, and update annually and when needed an assessment to determine resources necessary to care for its residents competently during both day-to-day operations and emergencies.

- Would include resident population (#, overall care needs and staff competencies required, cultural aspects); resources (e.g., equipment, and overall personnel); and a facility- and community-based risk assessment.

- Clinical Records – Would establish requirements that mirror some found in the HIPAA Privacy Rule (45 CFR part 160, and subparts A and E of part 164).

- Binding Arbitration Agreements

- Proposes specific requirements for the facility and the agreement itself to ensure that if a facility presents binding arbitration agreements to its residents that the agreements be explained and acknowledged regarding understanding; that they be entered into voluntarily; and arbitration sessions be conducted by a neutral arbitrator in a location that is convenient to both parties.

- Admission to the facility could not be contingent upon signing of a binding arbitration agreement.

- The agreement could not prohibit or discourage communication with federal, state, or local health care or health-related officials, including representatives of the Office of the State Long-Term Care Ombudsman.

- New Section: Quality assurance and performance improvement (QAPI) (§483.75)

- Would require all LTC facilities to develop, implement, and maintain an effective comprehensive, ongoing, data-driven QAPI programs that focus on systems of care, outcomes of care and quality of life.

- Facilities would submit the QAPI plan at the 1st standard survey after 1 year from the final rule effective date; and at each subsequent standard survey upon request; documentation and evidence of ongoing implementation also required upon request.

- Facilities would maintain effective feedback systems from staff, residents/resident representatives; establish priorities; have a process for identifying, reporting, analyzing, and preventing adverse/potential adverse events; systematic determination of underlying causes; measure/monitor the success of actions taken and track performance for sustainability; and include Performance Improvement Projects (PIPS).

- QAA Committee requirements would be maintained with amendment.

- Infection control (§483.80)

- Would require a system (Infection and Control Program – IPCP) for preventing, identifying, surveillance, investigating, and controlling infections and communicable diseases for residents, staff, volunteers, visitors, and other individuals providing services based upon facility and resident assessments as reviewed and updated annually; would also require incorporation of an antibiotic stewardship program.

- Would require designation of an Infection and Prevention Control Officer (IPCO) for whom the IPCP is their major responsibility and who would serve as a member of the facility’s quality assessment and assurance (QAA) committee.

- New Section: Compliance and ethics program (§483.85)

- Would require the operating organization for each facility to have in operation a compliance and ethics program with established written compliance and ethics standards, policies and procedures capable of reducing the prospect of criminal, civil, and administrative violations in accordance with section 1128I(b) of the Act.

- Required components: established written standards, policies, procedures; assignment of high-level personnel; sufficient resources and authority for these individuals; due diligence to prevent delegation to individuals with propensity for criminal, civil, administrative violations; effective communication and mandatory training; reasonable steps, e.g., monitoring/auditing systems, to achieve compliance; consistent enforcement; appropriate response to correct and prevent future occurrences.

- Physical environment (§483.90)

- Facilities initially certified after the effective date of this rule would be limited to two residents per bedroom.

- Facilities initially certified after the effective date of this rule would have to have a bathroom equipped with at least a toilet, sink and shower in each room.

- Would require policies, in accordance with applicable federal, state and local laws and regulations, regarding smoking, including tobacco cessation, smoking areas and safety.

- New Section: Training requirements (§483.95)

- Would add a new section setting forth all requirements of an effective training program for new and existing staff, contract staff, and volunteers. Proposed topics include effective communication; resident rights and facility responsibilities; abuse, neglect, and exploitation; QAPI & infection control; compliance and ethics.

- Annual training would be required for organizations operating five or more facilities.

- Would require dementia management and resident abuse prevention training as part of the 12 hours per year in-service training for nurse aides.

- Would require facilities to provide behavioral health training to all staff, based on the facility assessment.

- Focuses on facility responsibilities (protecting the residents’ rights, enhancing quality of life). This section parallels many residents’ rights provisions.

- CMS would retain all existing residents’ rights, but update language and organization to include, e.g., electronic communications. Proposed revisions would:

Learn more about how ALN Consulting can assist you in your Long Term Care cases.

Superbugs – The Growing Problem of Antibiotic Resistant Infections

Monday, August 31st, 2015

On August 04, 2015, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or CDC released a report published in their monthly Vital Signs[1] newsletter regarding the increasing number of germs that no longer respond to the drugs designed to kill them. The report notes that inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics and lack of infection control actions can contribute to drug resistance and put patients at risk. Despite diligent precautions which may be implemented by one facility, these germs can be spread between health care facilities when patients are transferred from one to another.

The most common and deadliest of these superbug infections include carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriacae or CRE which can cause deadly infections and have become resistant to nearly all antibiotics that we currently have in use. Perhaps the most commonly known antibiotic resistant infection methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus or MRSA often causes pneumonia and sepsis. Also infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa which can result in healthcare associated infection include strains that are resistant to almost all antibiotics. Clostridium difficile also known as ‘C. diff’ is a germ commonly found in health care facilities and is not resistant to antibiotics but results from antibiotic use killing the bodies “good germs” and allowing this bacterium to take over putting patients at high risk for deadly diarrhea.

In order to reduce the number of antibiotic resistant infections the CDC recommends beginning with implementation of systems to alert receiving facilities when transferring patients who have drug resistant germs as well as sharing data with the public health department about antibiotic resistance and other healthcare associated infections.

The CDC released these statistics in relation to the growing problems of antibiotic resistant infections:

- Antibiotic-resistant germs cause more than 2 million illnesses and at least 23,000 deaths each year in the US.

- Up to 70% fewer patients will get CRE over 5 years if facilities coordinate to protect patients.

- Preventing infections and improving antibiotic prescribing could avert 610,000 infections and save 37,000 lives from drug-resistant infections over 5 years. This would save the health care system nearly 8 billion dollars for treatment.

Source: CDC Vital Signs, August 2015

Source: CDC Vital Signs, August 2015

A study cited by the CDC where researchers think a more coordinated approach may be working included the South Dakota public health department which requires health care facilities to report cases of CRE for tracking the spread of the bacteria. Infections caused by the deadly bacteria in that sparsely populated state dropped from 24 to 4 over two years. In Illinois, the state health department maintains a registry of all patients infected with drug-resistant bacteria. When a hospital or nursing home admits a patient, the facility can check the registry to see if the patient has an infection and take the appropriate precautions to prevent transmission.